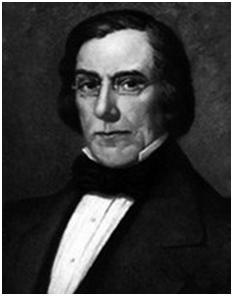

Born in Strafford County, Virginia, on April 24, 1784, into a prominent Virginia family, Daniel attended the College of New Jersey briefly before settling in Richmond to read law with former attorney general and founding father Edmund Randolph. Two years after being admitted to the Virginia bar in 1808, Daniel married Randolph’s daughter Lucy. He gained election to the Virginia House of Delegates from Stafford County in 1809. Three years later the assembly elevated him to the Privy Council, the governor’s advisory body, where for much of his twenty-three-year tenure he served as lieutenant governor.

Born in Strafford County, Virginia, on April 24, 1784, into a prominent Virginia family, Daniel attended the College of New Jersey briefly before settling in Richmond to read law with former attorney general and founding father Edmund Randolph. Two years after being admitted to the Virginia bar in 1808, Daniel married Randolph’s daughter Lucy. He gained election to the Virginia House of Delegates from Stafford County in 1809. Three years later the assembly elevated him to the Privy Council, the governor’s advisory body, where for much of his twenty-three-year tenure he served as lieutenant governor.

As an attorney in Richmond, Daniel enjoyed modest success. Politically active, he was admitted to the Richmond Junto, through which he organized and led the Old Dominion’s Jacksonian Democrats. In recognition of his party loyalty and support of the bank war, Andrew Jackson in 1836 appointed Daniel judge of the US District Court for Eastern Virginia.

When Associate Justice Philip P. Barbour died suddenly in February 1841, outgoing President Martin Van Buren hurriedly seized the opportunity to nominate his friend Daniel to the court. Despite the efforts of Whig senators to thwart this move, Daniel was confirmed about midnight of March 2-3, 1841.

Selected more for his political faithfulness than his legal ability or judicial stature, Daniel joined the court in December 1841 unswervingly opposed to banks, corporations, and economic consolidation of any sort; an extreme defender of states’ rights, limited government, and the institution of slavery; and consumed with a hatred for anything northern. As a justice he consistently opposed the expansion of federal regulatory or jurisdictional authority and resisted the doctrine of federal exclusiveness under the commerce clause.

Fearful of the growing power of corporations, Daniel declared such chartered bodies to be artificial persons and thus not entitled to standing in federal courts on the basis of diversity of citizenship. In his strongly worded dissent in Planters’ Bank of Mississippi v. Sharp (1848), he opposed application of the contracts clause to corporate charters, arguing that contracts remained subject to the police power of the states.

Daniel’s majority opinion in West River Bridge Co. v. Dix (1849) held that a state must have the power, under the doctrine of eminent domain, to condemn any property, whether corporate or unincorporated, for public use. He also joined the majority in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), in which his concurring opinion declared that freed black slaves, because they had been originally held as property, could not be citizens.

Highly principled but markedly out of step with the legal and constitutional developments of his day, Daniel was doomed to stand his ground with carefully articulated but extreme opinions that ultimately left little mark on American constitutional law.

He died on May 31, 1860.

Sources of information: John P. Frank, Justice Daniel Dissenting: A Biography of Peter V. Daniel, 1784-1860 E. Lee Shepar, 1964.