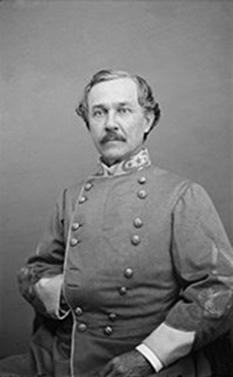

Joseph Reid Anderson was an iron manufacturer and Confederate army officer during the American Civil War (1861–1865). In 1848 he purchased the Tredegar Iron Company, the largest producer of munitions, cannon, railroad iron, steam engines, and other ordnance for the Confederate government during the Civil War. One of Anderson’s most notable decisions was to introduce slaves into skilled industrial work at the ironworks, and by 1864 more than half the workers at Tredegar were bondsmen. Anderson served as a brigadier general for the Confederate army, and fought and was wounded during the Seven Days’ Battles. He resigned his commission in the Confederate army in 1862 to resume control of the ironworks, and after the war Anderson was a strong proponent for peace, hoping to keep the Union army from taking possession of the ironworks. He failed but regained control of Tredegar after President Andrew Johnson pardoned him in 1865. By 1873 Anderson had doubled the factory’s prewar capacity, and its labor force exceeded one thousand men, many of them black laborers and skilled workmen who received equal pay with white workers. Though Tredegar failed to make the transition from iron to steel production late in the nineteenth century, the company survived into the 1980s. Anderson was a well-known member of the Richmond community, serving multiple terms on the Richmond City Council and in the House of Delegates before and after the war.

Joseph Reid Anderson was an iron manufacturer and Confederate army officer during the American Civil War (1861–1865). In 1848 he purchased the Tredegar Iron Company, the largest producer of munitions, cannon, railroad iron, steam engines, and other ordnance for the Confederate government during the Civil War. One of Anderson’s most notable decisions was to introduce slaves into skilled industrial work at the ironworks, and by 1864 more than half the workers at Tredegar were bondsmen. Anderson served as a brigadier general for the Confederate army, and fought and was wounded during the Seven Days’ Battles. He resigned his commission in the Confederate army in 1862 to resume control of the ironworks, and after the war Anderson was a strong proponent for peace, hoping to keep the Union army from taking possession of the ironworks. He failed but regained control of Tredegar after President Andrew Johnson pardoned him in 1865. By 1873 Anderson had doubled the factory’s prewar capacity, and its labor force exceeded one thousand men, many of them black laborers and skilled workmen who received equal pay with white workers. Though Tredegar failed to make the transition from iron to steel production late in the nineteenth century, the company survived into the 1980s. Anderson was a well-known member of the Richmond community, serving multiple terms on the Richmond City Council and in the House of Delegates before and after the war.

Joseph Reid Anderson was born on February 16, 1813, at Walnut Hill in Botetourt County, the fifth of six sons and ninth of ten children of William Anderson and Anna Thomas Anderson. He attended a school in nearby Fincastle and received an appointment to the US Military Academy at West Point, from which he graduated in 1836, fourth in a class of forty-nine. He served briefly in the 3rd Artillery, US Army, before being assigned to engineering duties and was later transferred to the Corps of Engineers. He served in Washington, DC, at Fort Monroe in Virginia, and at Fort Pulaski in Georgia, but he lost interest in a military career soon after he married Sarah Eliza Archer of Norfolk in May 1837. In September 1837 he resigned his commission. The Andersons had five sons and seven daughters, of whom three sons and four daughters reached adulthood.

In the autumn of 1837, Anderson became an assistant state engineer in the construction of the Valley Turnpike between Staunton and Winchester, service that stimulated his interest in Virginia’s economic development. He promoted the construction of canals and railroads to connect the Valley of Virginia to Tidewater Virginia, and his concern for internal improvements led him into the southern commercial convention movement and into the Whig Party. Those activities brought him to the attention of the owners of Richmond’s Tredegar Iron Company. He became the company’s commercial agent in March 1841 and remained associated with Tredegar until his death. At the time Anderson joined Tredegar, the four-year-old company was in financial difficulty. He actively sought and obtained contracts with the federal government to manufacture munitions and other supplies for the army and navy and rapidly brought about an improvement in the company’s fortunes. During the next two decades, Tredegar produced 881 cannons for the armed forces, an iron revenue cutter for the Treasury Department, and engines and boilers for two navy frigates. As Tredegar became profitable, Anderson tired of the board of directors’ meddling in technical matters, and in November 1843 he leased the entire ironworks for five years. Anderson prospered as superintendent of Tredegar and also from 1846 to 1848 as president of the Armory Iron Company. In April 1848 he purchased the Tredegar Iron Company and assumed complete control over all phases of the work.

One of Anderson’s most notable innovations was the introduction of slaves in skilled industrial work. He began using bondsmen in unskilled jobs in 1842, and in 1847 he proposed using them in skilled work at the Armory rolling mill. When the skilled white workers, many of whom were northern- or foreign-born, responded with strikes at both the Armory and Tredegar rolling mills, Anderson fired the strikers and put slaves in skilled jobs at both establishments. The replacements successfully demonstrated their ability to perform such labor. The company owned many of them and hired others from local owners, but despite Anderson’s determination to employ skilled slaves, he continued to rely heavily on northern and European immigrant workers, with whites constituting the vast majority of his workforce in 1860.

Through his success in making Tredegar the largest ironworks in the South and one of the largest in the United States, Anderson became one of the region’s leading industrialists.

Although Tredegar produced a substantial amount of armaments for the government, the largest part of its production was railroad iron. Tredegar also turned out a wide variety of finished iron products, including steam engines for gristmills, sawmills, and sugar mills, and iron for bridges. By 1860 the Tredegar workforce of about eight hundred was the fourth largest of any American ironworks. In the face of competition from northern mills and from England, Anderson entered into a series of partnerships that permitted him to complete the payments on the purchase of Tredegar in 1856, and in 1859 he formed Joseph R. Anderson and Company, combining Tredegar with Archer and Company, a rolling mill that Anderson’s father-in-law and brother-in-law owned.

Anderson was elected to the Richmond City Council in 1847 and served five terms before the Civil War. In 1852 he was elected to a vacant seat in the House of Delegates and was reelected in 1853. He served on the Committee on Roads and Internal Navigation and promoted state support for the construction of railroads and canals. Following the collapse of the Whig Party, Anderson became a Democrat. He was elected to the House of Delegates again in 1857, but he was defeated in 1859. After Abraham Lincoln was elected president in November 1860, Anderson advocated secession and actively promoted the sale of arms to the Southern states. Tredegar sold munitions to South Carolina during the Fort Sumter crisis and geared up to increase arms production. Anderson also negotiated arms contracts with the provisional government of the Confederacy. He was a member of a Southern rights convention that met in Richmond on April 17, 1861, and that would have passed an extralegal secession ordinance if the Virginia convention had not done so that day. When Virginia left the Union, Anderson offered to turn Tredegar over to the Confederate government by lease or purchase, but the government declined the offer.

In May 1861, Anderson organized 350 of his white workmen into a home defense unit known as the Tredegar Battalion, which he commanded with the rank of major. On August 21 he requested a commission in the Confederate army, and on September 3, 1861, he was appointed a brigadier general. He commanded the District of Cape Fear, North Carolina, from September 30, 1861, to March 19, 1862, and the Department of North Carolina from March 19 to 24, 1862. He led a brigade at Fredericksburg in April and May, and a brigade in A. P. Hill’s division during the Seven Days’ Battles. Anderson was slightly wounded in the face on June 30, 1862. He temporarily commanded Hill’s division from July 13 to 19, 1862, when he resigned his commission to resume management of the Tredegar ironworks.

Tredegar was the largest supplier of arms and other iron products to the Confederate government and produced 1,099 cannons during the war. Tredegar also produced armor plate and machinery for Confederate warships, including the CSS Virginia; artillery shot and shells; machinery and tools for the production of small arms by other armories, for the powder mill at Augusta, Georgia, and for the naval ordnance plant at Charlotte, North Carolina; and an armor-plated railroad car mounting heavy cannons. Tredegar was also a major supplier of iron for Southern railroads. The company grew enormously during the war. It expanded the Richmond plant, acquired blast furnaces to produce pig iron, and purchased coal mines to supply the furnaces. The total workforce rose as high as twenty-five hundred men, and Anderson increased the use of slave labor after many of the white workers entered military service or fled the Confederacy. By 1864 more than half of the workers were slaves, many filling skilled positions. Even though food shortages became widespread in the Confederacy, Tredegar fed not only its slaves but also its white employees and their families, to whom it sold food at cost.

Anderson and his partners also purchased large quantities of cotton during the war and shipped them to European markets on blockade runners, including a ship called the “Coquette” that they purchased from the Confederate navy in 1864. Anderson insisted that the cotton sales were used to finance greater production of military and railroad supplies at Tredegar, but most of the money went into a sterling account in London, and Anderson used those funds to keep control of Tredegar after the war.

Following the fall of Richmond on April 3, 1865, Anderson became a strong peace advocate. He and other Richmond leaders met with Abraham Lincoln in the city on April 4 to discuss how to end the war, and Anderson headed a citizens’ commission to call the General Assembly into session to take Virginia out of the Confederacy. By taking part in the peace movement, Anderson hoped to keep the Union army from taking possession of the ironworks, but he was unsuccessful even though the surrender of the Confederate army brought a speedy end to the war. Anderson enlisted the aid of many prominent southern Unionists and Virginia railroad executives,—and even some northern businessmen and Richmond African Americans,—and obtained a pardon from President Andrew Johnson on September 21, 1865.

Anderson regained control of Tredegar after being pardoned, but the company remained in financial difficulty, and he had trouble attracting new capital. In February 1867 he and his son Archer Anderson and three other partners reorganized the venture as Tredegar Company, with Joseph Reid Anderson as the majority stockholder. The reorganization enabled Tredegar to attract northern capital and expand its operations. By 1873 Anderson had doubled the factory’s prewar capacity, and its labor force exceeded one thousand men, many of them black laborers and skilled workmen who received equal pay with the whites. The panic of 1873 and the resulting depression forced Tredegar into receivership in 1876. Anderson served as receiver of the company until September 1879, when the company successfully funded its debt, but Tredegar failed to make the transition from iron to steel production late in the nineteenth century, It lost its position as one of the premier southern industrial enterprises, although the Richmond plant continued in operation until the 1950s and the company survived as a manufacturing entity into the 1980s.

Anderson remained one of Richmond’s most successful and famous citizens. He returned to public life in the 1870s and served in the House of Delegates in 1874 and 1875 and again from 1877 to 1879. He was president of the Richmond Chamber of Commerce from 1874 to 1876, when he resigned to become president of the Richmond City Council. Anderson served on the vestry of Saint Paul’s Episcopal Church from 1844 until his death and was a senior warden for twenty-one years. Following the death of Sarah Eliza Archer Anderson in 1881, he married Mary E. Pegram of Richmond in November 1882. After a period of poor health, Joseph Reid Anderson died on September 7, 1892, while visiting Isles of Shoals, New Hampshire.

Source of information: The Dictionary of Virginia Biography. Joseph Reid Anderson (1813-1892). Retrieved February 2, 2013, from Encyclopedia Virginia: http://www.EncyclopediaVirginia.org/Anderson_Joseph_Reid_1813-1892.