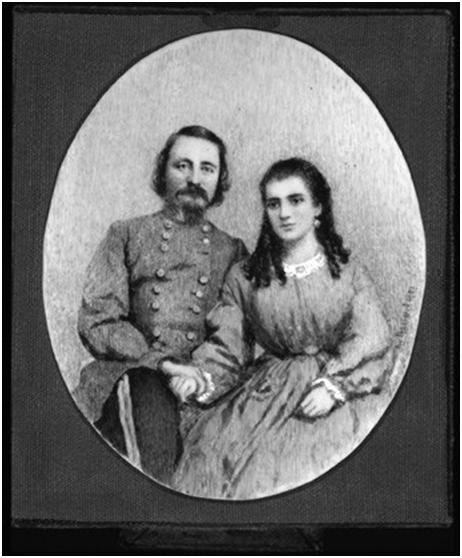

George E. Pickett was a Confederate general during the American Civil War (1861–1865) and one of the most controversial leaders in the Army of Northern Virginia. Described by his admirers as swashbuckling, he was famous for his tailored uniforms, gold spurs, and shoulder-length brown hair. (His contemporary admirers were relatively few in number, however, and this image of Pickett is likely more myth than fact.) Confederate Gen. James Longstreet commented on his friend’s “wondrous pulchritude and magnetic presence” and is said to have mentored Pickett, who was last in his class at West Point. At Gettysburg (1863), Pickett’s name became permanently linked, in both fact and myth, with Pickett’s Charge, the doomed frontal assault on the battle’s third day. He had little responsibility for the attack’s planning or its failure, and the loss of his division, which he partly blamed on Robert E. Lee, devastated him. Accused of war crimes for executing twenty-two Union prisoners in 1864, Pickett ended the war broken and in bad health. His reputation, however, was thoroughly rehabilitated after his death by his third wife, LaSalle Corbell Pickett, whose writings turned the often incompetent general into an idealized “Lost Cause” hero.

George E. Pickett was a Confederate general during the American Civil War (1861–1865) and one of the most controversial leaders in the Army of Northern Virginia. Described by his admirers as swashbuckling, he was famous for his tailored uniforms, gold spurs, and shoulder-length brown hair. (His contemporary admirers were relatively few in number, however, and this image of Pickett is likely more myth than fact.) Confederate Gen. James Longstreet commented on his friend’s “wondrous pulchritude and magnetic presence” and is said to have mentored Pickett, who was last in his class at West Point. At Gettysburg (1863), Pickett’s name became permanently linked, in both fact and myth, with Pickett’s Charge, the doomed frontal assault on the battle’s third day. He had little responsibility for the attack’s planning or its failure, and the loss of his division, which he partly blamed on Robert E. Lee, devastated him. Accused of war crimes for executing twenty-two Union prisoners in 1864, Pickett ended the war broken and in bad health. His reputation, however, was thoroughly rehabilitated after his death by his third wife, LaSalle Corbell Pickett, whose writings turned the often incompetent general into an idealized “Lost Cause” hero.

George Edward Pickett was born on January 16, 1825, and raised on his family’s plantation at Turkey Island in Henrico County. He attended the US Military Academy at West Point, accumulating a host of demerits and graduating last in his class in 1846. (Pickett’s classmates included Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson and George B. McClellan.) He went on to serve in the Mexican War (1846–1848), earning two honorary brevets for gallant conduct.

Pickett spent the next thirteen years in the frontier army, in scattered outposts in Texas and in the far West. During these years, he faced personal tragedies. In November 1851, his first wife, Sally Minge, and their newborn daughter died in Texas. While stationed at Fort Bellingham in Washington Territory and finding himself frequently caught between the interests of white settlers and Indians, he married a Haida Indian. She also died, however, soon after the birth of their son, James Tilton Pickett, in 1857.

The Civil War brought Pickett home to Virginia to fight for the Confederacy. By the spring of 1862, he led an all-Virginia brigade under the command of his old army friend James Longstreet. Pickett fought ably in the battles of Williamsburg (1862) and Seven Pines (1862), earning commendations from his superiors. At the battle of Gaines’s Mill (1862), Pickett was severely wounded and, as a result, left active service for the rest of the summer. He returned to the field in the autumn of 1862, winning promotion to major general. Pickett and his division remained largely in reserve during the lopsided Confederate victory at Fredericksburg (1862) and did not participate at all in the stunning victory at Chancellorsville (1863). His division was instead with Longstreet, laying siege to Suffolk. It was there, however, that Pickett became increasingly distracted by his courtship with LaSalle Corbell. They married in St. Paul’s Church in Petersburg on September 15, 1863, just a few weeks after the fateful Battle of Gettysburg.

Judged by many to be the turning point of the Civil War, Gettysburg was also a crucial turning point for Pickett. He entered that battle seeking to prove himself as a division leader and to quiet detractors who had begun to question his courage. Instead the battle only caused more doubt. Pickett’s division had been slow to reach Gettysburg and so had missed the bloody but indecisive fighting on July 1 and 2. Because they were fresh, Lee chose Pickett’s Virginians, along with two other divisions, to lead the charge on Cemetery Ridge, which began shortly after three o’clock in the afternoon. It was a fiasco. The casualty rate was more than 50 percent—higher than at Cold Harbor (1864)—and all of Pickett’s brigade and regimental commanders were either killed or wounded. The general watched in tears as his division broke and shattered before him. He spent the rest of the war, and the rest of his life, brooding over the loss.

After Gettysburg, Pickett assumed command of the Department of North Carolina, an assignment made difficult by high rates of desertion, Unionist sentiment in the area, and guerrilla warfare. His situation went from bad to worse. In February 1864, Lee ordered him to take the coastal city of New Berne, North Carolina, from Union control. Pickett faltered and failed, and in his report he lashed out at fellow officers. Pickett also discovered that a group of Union prisoners were, in fact, former Confederate soldiers who had switched sides. He angrily ordered them tried by court-martial, and twenty-two were summarily hanged in Kinston, North Carolina, as their family and friends stood witness. Their bodies were stripped and buried in an unmarked mass grave.

Pickett rejoined the Army of Northern Virginia in May 1864, even regaining his old division, but nothing was the same. The last ignoble chapter of his military career came on April 1, 1865. At the battle of Five Forks, Union troops successfully attacked Lee’s right flank, ending their ten-month siege and forcing the fall of Petersburg and the Confederate capital of Richmond. Pickett, however, left his troops poorly positioned for the fight when he left the lines for an infamously long lunch—a shad bake with Fitzhugh Lee, Robert E. Lee’s nephew. The “food was abundant,” the historian Douglas Southall Freeman has written, and “the affair was leisured and deliberate as every feast should be.” In the meantime, the battle was lost and Pickett was removed from command. The surrender at Appomattox Court House came just eight days later on April 9.

Pickett returned home to discover that the US War Department was investigating him for war crimes for the Kinston hangings. With his wife and infant son, he escaped to Montreal, Canada, but returned to Virginia after a few months when Ulysses S. Grant indicated that there would be no formal indictment. He lived there quietly and modestly, farming, selling insurance, and battling declining health. Pickett rarely spoke publicly about his war experiences and died on July 30, 1875, at the age of fifty.

While the former general had spent his last years brooding about the disastrous charge that bore his name, his financially burdened widow decided to make the most of an opportunity. In an attempt to revitalize his memory, she became a prolific author and widely traveled lecturer, transforming Pickett into the hero of Gettysburg in the tradition of the “Lost Cause.” The Lost Cause was a view of the war that downplayed slavery and lionized the Confederate military. It is ironic, perhaps, that Pickett should so benefit from the pens of Lost Cause writers while his friend and mentor, James Longstreet, so suffered. Longstreet, who became a Republican Party member after the war, was blamed for the defeat at Gettysburg by former Confederate Gen. Jubal A. Early, among others.

LaSalle Corbell Pickett authored the celebratory history Pickett and His Men (1913), which the historian Gary W. Gallagher has demonstrated was largely plagiarized, and two collections of wartime letters (1913 and 1928), which Gallagher has argued were fabricated. Nevertheless, her image of her husband at the moment his charge began—“gallant and graceful as a knight of chivalry riding to a tournament,” whose “long, dark, auburntinted hair floated backward in the wind like a soft veil as he went on down the slope of death”—has stuck in the American imagination. And her letters have been cited in works as diverse as Michael Shaara’s Pulitzer Prize–winning novel, The Killer Angels (1974), and Ken Burns’s documentary The Civil War (1990).

Sources of information: APA Citation: Gordon, L. J. (Dec. 4, 2012). George E. Pickett (1825-1875). Retrieved Feb. 10, 2013, from Encyclopedia Virginia: http://www.EncyclopediaVirginia.org/Pickett_George_E_1825-1875.