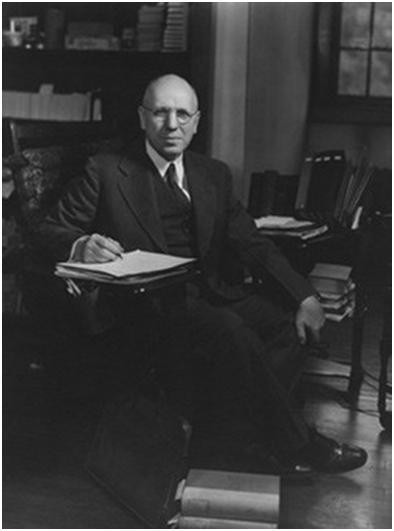

Douglas Southall Freeman was a biographer, a newspaper editor, a nationally renowned military analyst, and a pioneering radio broadcaster. He won the Pulitzer Prize twice: the first, in 1935, for his four-volume biography of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee; and the second, posthumously in 1958, for his six-volume biography of George Washington (with a seventh volume written by John Alexander Carroll and Mary Wells Ashworth after Freeman's death in 1953). The son of a Confederate veteran, Freeman is best known as a historian of the American Civil War and, in particular, of the high command of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. His description of Lee, Thomas J. "Stonewall Jackson, and their compatriots as "men of principles unimpeachable, of valor indescribable" for some has suggested that his work was influenced by the Lost Cause view of the war that was, in part, founded by his former neighbor Jubal A. Early. In reality, Freeman's admiration for the Confederates never influenced his historical conclusions.

Douglas Southall Freeman was a biographer, a newspaper editor, a nationally renowned military analyst, and a pioneering radio broadcaster. He won the Pulitzer Prize twice: the first, in 1935, for his four-volume biography of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee; and the second, posthumously in 1958, for his six-volume biography of George Washington (with a seventh volume written by John Alexander Carroll and Mary Wells Ashworth after Freeman's death in 1953). The son of a Confederate veteran, Freeman is best known as a historian of the American Civil War and, in particular, of the high command of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. His description of Lee, Thomas J. "Stonewall Jackson, and their compatriots as "men of principles unimpeachable, of valor indescribable" for some has suggested that his work was influenced by the Lost Cause view of the war that was, in part, founded by his former neighbor Jubal A. Early. In reality, Freeman's admiration for the Confederates never influenced his historical conclusions.

Freeman was born on May 16, 1886, in Lynchburg, Virginia, to Bettie Allen Hamner and Walker Burford Freeman, an insurance agent who had served four years in Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. In 1892 the family moved to the former Confederate capital of Richmond, which was then at the height of a commemoration movement. Surrounded by a passionate discourse about the Civil War, Freeman developed an emotional and intellectual devotion to southern history and heritage. In Lynchburg, his family had lived down the street from the former Confederate general Jubal Early, whom Freeman would later describe as "snarling and stooped" and whom Freeman's daughter would say had inadvertently terrified the young Freeman. Nevertheless, Freeman's respect for men like Early would characterize his later scholarship.

Freeman studied first at Richmond College (now the University of Richmond), receiving a bachelor of arts degree in 1904, and then at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, where in 1908 he earned a doctorate in history with the goal of writing an account of Lee and his army. His first book, the bibliographic survey A Calendar of Confederate Papers, was published in 1908. Freeman attempted to get a job in academia, but in the end he joined the staff of the Richmond Times-Dispatch in 1909. He was briefly secretary of the State Tax Commission, and in mid-1914, after the Times-Dispatch was sold, he hired on at the Richmond News Leader.

Then, in 1911, an acquaintance unexpectedly delivered to him a cache of long-lost wartime communication between Lee and Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Lee's Dispatches (1915) turned Freeman into an overnight sensation among Confederate historians and led to an invitation from the New York publisher Charles Scribner's Sons to write a biography of Lee. Rather than surrender any of his journalistic responsibilities -- after an astounding rise, he became editor of the News Leader in 1915 -- Freeman instead worked longer days. He researched Lee exhaustively and narrated the general's Civil War years using what came to be known as the "fog of war" technique. By providing readers only the limited information that Lee himself had a given point, Freeman emphasized the confusion of war and the process by which Lee grappled with problems and made decisions.

R. E. Lee appeared in four volumes in 1934-1935. The New York Times judged the work "Lee Complete for All Time," and Freeman was awarded the 1935 Pulitzer Prize for biography. The work established the foundation for the "Virginia School" of Civil War scholarship, marked by an emphasis on the eastern theater of the war and an attention to generals at the expense of fighting men. Freeman's books also showed a preference for campaigns over social and political history and a sympathy for his Confederate subjects that was, perhaps, greater than that of many later historians. This has provoked some critics into labeling Freeman as a "Lost Cause historian." There is no doubt that Freeman greatly admired Lee and his contemporaries. There is no doubt that he was partisan in his sympathies. The key difference, though, between Freeman and Jubal Early (and those of the Lost Cause school) is that Freeman's personal admiration did not impact his conclusions. There is not one significant statement of fact in R. E. Lee that has been successfully challenged by modern historians. Moreover, matters on which Freeman speculated have been confirmed by subsequently discovered documents. More than seventy years later, R. E. Lee remains the authoritative study on the Confederate general.

Freeman followed his biography of Lee with the critically acclaimed three-volume Lee's Lieutenants (1942 - 1944), a distinctive combination of military strategy, multiple biography, and Civil War history. This work established him as the nation's preeminent military historian and led to close friendships with US generals George C. Marshall and Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Freeman's literary achievements have overshadowed his career as editor of the News Leader. He wrote six hundred thousand words of editorial copy every year from 1915 until 1949, earning national acclaim for his analyses of military operations. His editorials expressed a moderate, albeit paternalistic, approach to race relations, and he was considered an opponent of the Byrd Organization, US Senator Harry F. Byrd Sr.'s powerful statewide Democratic political machine. He instituted the "Twenty fundamental rules of news writing," which directed his reporters to "above all, be clear." Freeman's editorial duties also included two daily radio newscasts.

Having completed his study of the Confederate war effort, Freeman turned to a biography of George Washington. He completed six volumes, a seventh was released after his death, and the entire work was awarded a posthumous Pulitzer Prize. Freeman's other works include The South to Posterity: An Introduction to the Writings of Confederate History (1939) and Lee of Virginia (1958).

In addition to writing, Freeman taught journalism at Columbia University in New York, conducted a weekly current-events class, and served as rector of the University of Richmond. To meet his myriad obligations, he adopted a schedule that started his day well before dawn and scripted his every moment. Wise use of time, he said, made the difference "between drudgery and happiness, between existence and career."

Freeman retired from the News Leader in 1949 to complete Washington and start a study of World War II (1939 - 1945). He died of a heart attack on June 13, 1953, at his home, Westbourne. According to his obituary in the New York Times, he had been "up at his usual hour of 2:30" that morning "and made his daily radio commentary on the news at 8 a.m."

Source of information: Information about Douglas Freeman was contributed by David Johnson and is courtesy of Library of Virginia, a publication of the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities in partnership with Library of Virginia.